How Japan failed to harness wind power

Most recent

Japan can quickly ramp up its wind energy capacity with offshore wind farms. Instead, the country is performing below average compared to other developed nations.

Japan is in a unique geographical location where it can quickly ramp up wind energy to decrease its reliance on fossil fuel imports and transition to renewable energy. But, so far the Japanese government has yet to take meaningful action, falling behind on other developed nations and relying for 88% of its energy supply on imported fossil fuels. In 2021, Japan ranked 21st in terms of wind power capacity. Why didn’t Japan take this opportunity and are there signs of change?

Energy security in Japan

In 2017, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) released a report which suggested that Japan could stabilize its energy mix through greater adoption of renewable energy. The organization said that wind-power resources are abundant, but the country has so far withheld any meaningful action in this field, especially in terms of off-shore wind adoption. Its large manufacturing industries could enable Japan to quickly ramp up the production of wind turbines, which could airlift into exponentially increasing its wind power capacity and adoption of renewable energy overall.

This statement was reinforced by Daisuke Akimoto, who wrote a piece for The Diplomat in 2022, stating that recent geopolitical developments such as the war in Ukraine highlighted the need for the Japanese government to increase investments in wind energy to decrease the reliance on imported fuel sources. This rang especially true when the Prime Minister of Japan, Kishida Fumio revealed that investments into two fossil fuel projects in Russia, the Sakhalin-1 and Sakhalin-2 would remain, solidifying its reliance on a foreign adversary evermore. Hagiuda Koichi, the Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry, defended the decision stating that collaborating on these projects would secure Japan’s energy needs as prices soared.

Slow adoption of renewables in Japan

To this day, Japan remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels. The IEA revealed that Japan relied for 88% of its energy supply on imported fossil fuels in 2019, ranking it sixth highest among the IEA countries. This energy mix won’t come as a novelty, but the lack of action raises questions.

In 2020, Yun Tzu Lin at Climate Scorecard wrote that Japan wasn’t investing enough in renewable energy, making it fall behind on its energy sector decarbonization efforts. Lin points out that Japan has been reluctant to scale back its coal-powered plants. The need for coal plants was reignited after the accelerated shutdown of its nuclear plants after the Fukushima nuclear reactor meltdown. As a result, the government scrambled to fill the demand, announcing in 2020 that it would build 22 new coal plants with 17 just in the coming five years.

The plans to build new coal plants are in stark contrast with the impact of global warming on Japan, which is experiencing severe heat waves in recent years. In 2018, an unprecedented heat wave was estimated to have resulted in the premature death of around 1,000 people. Scientists argue that these temperatures couldn’t occur without climate change. Kimiko Hirata, Director of the climate action group, Kiko Network, said to the New York Times that on one hand, the Japanese government is advertising the low emissions of the Olympics, whilst on the other hand opening new coal plants that nullify all efforts made for the Olympics.

Japanese banks love coal

The previous sections paint a gloomy picture. The Japanese government has been solely focusing on importing fossil fuels and drafting plans at breakneck speeds to open up nearly two dozen new coal plants to fill the gap in its reduced nuclear energy supply. One of the main reasons for the lack of investments in renewable energy and wind power, in particular, is Japan’s love for coal.

Back in 2008, Green Tech Media reported on the brittle commitment to increasing renewable energy. Despite hosting the Kyoto Protocol climate convention, the country has done, unsurprisingly, very little to combat carbon emissions. Investments in wind energy had nearly stopped to a halt, with Japan finding itself in the fourteenth spot in the Global Wind Energy Council rankings for yearly growth in wind capacity. President of the Japanese-based Green Power Investment Corp., Toshio Hori, told Green Tech Media, “Japan’s wind power industry is not growing. […] The renewable targets the government has set for wind power are tiny in comparison to other countries. There are no incentives for companies to grow.”

Green Tech Media points to the lack of action in terms of governmental policy and incentives that foster a financial framework for wider commercial adoption of renewable energy, which in turn have resulted in decreases in carbon emissions. This has had the opposite effect instead. The carbon reduction targets were so low in fact, that the ambitions of even the most dedicated fossil fuel lobbyist, looked far more promising. At that point in time, Japan wasn’t on track to reduce its carbon emissions by a measly 6 percent in 2010, compared to 1990 levels. The reasons why Japan is struggling with wind energy, and renewable energy, adoption can be found elsewhere. In the banking sector.

In 2019, the Rainforest Action Group (RAN) found that three major Japanese banks, MUFG, Mizuho, and the SMBC Group, were responsible for the rapidly expanding coal power industry, within Japan and in other parts of the world. RAN referenced investments made in the J-POWER-developed Nishioki No Yama coal power plant, which received a large portion of its financing from the three earlier-mentioned banks. The trio also invests in projects across southeast Asia, in countries like Indonesia and Vietnam.

The Sumitomo Corporation was anticipated to finance the 1.3 GW capacity Van Phong 1 coal power plant in Vietnam, which is expected to emit five times more greenhouse gas emissions than its modern Japanese counterparts. Japanese bank Marubeni, in cooperation with the Korea Electric Power Company, is realizing an additional 1.2 GW coal plant in Vietnam, Nghi Son 2, situated in the Thanh Hóa province. Banks across Asia have been warned against the project, as it will be a large emitter of greenhouse gas. The increasing amount of emissions also poses a threat to public health.

A study released in the journal for Environmental Science and Technology found that the rise in greenhouse gas emissions through coal-fired power plants results in an increase in diseases and higher mortality rates. The team, a consortium of researchers at Harvard, Greenpeace, and the University of Colorado, reported that through the opening of multiple coal power plants throughout south-east Asia, the number of emissions is set to triple by 2030, with the largest increases expected in countries like Indonesia and Vietnam. The same countries where Japanese banks are pouring their money. This pattern can be traced back to active lobby groups that dictate the course of climate policy and secure business interests in maintaining the status quo.

Strong lobbyists

Reuters headlined a report published by data analysis firm InfluenceMap in 2020. The London-based company discovered that Japanese business lobby Keidanren, which represents just a small fraction of the Japanese economy, keeps pressuring the Japanese government to keep investing in fossil fuel projects. In doing so, resulting in the government shying away from driving any meaningful action in terms of renewable energy adoption. InfluenceMap found that lobbyists at Keidanren had intimate ties with influential governmental institutions, sitting at the negotiation table for two decades. Heavily influencing Japanese climate policy.

The findings were backed by Hikaru Kobayashi, former Vice-Minister at the Ministry of the Environment, who told Reuters, “[…] mostly consistent with my personal experience as a policymaker in Japan to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol and to develop national legislation.” Remarking that he is surprised not much had changed ever since. But in a surprising turn of events, the government pulled out of several coal power plant investments abroad.

In June 2022, the Japanese government announced it would stop further investments in two planned coal-fired power plants in Bangladesh and Indonesia. The redraw of funding is a u-turn in the country’s earlier commitment to keep investing in fossil fuel projects around the world. The immediate funding stop is a response to a G7 commitment made in 2021, where top economies pledged to not invest in foreign coal power projects in an effort to reduce carbon emissions.

Offshore wind energy

Despite all the negative press that Japan has been collecting in terms of its energy policy, there are subtle signs that things are changing. In 2012, the country introduced the Feed-In-Tariff (FIT) program, which would guarantee a return on investors for those committing to renewable energy projects. The first signs can be traced back to the drop in solar panel costs which have dropped by upwards of 30 percent from 2012 to 2017. FIT also included incentives for small wind power projects and was ramped up in 2017 to also include larger on- and offshore wind energy projects.

As construction of the first large commercial wind farm along the coast of Akita started, McKinsey highlighted that this could be the beacon for a new dawn for Japanese wind offshore wind energy. Hundred billion yen ($670 million) were allocated towards the construction of two wind farms in Akita, which combined would deliver 140 MW of electricity, able to supply 150,000 Japanese homes with renewable energy. McKinsey says that once offshore wind farms will see wider adoption, the annual nation’s fuel bill can be reduced by $300 million. As industries will switch over to wind and other renewables, prices will start to drop, making fossil fuels less economical. But, the consulting firm notes that several hurdles will have to be overcome.

The relatively hostile environment poses several challenges for wind farms. Deepwater, steep coastlines, and variable wind speeds make wind energy expensive. Project developers should therefore focus on nearshore projects, which are less prone to these variables. Legislation has been revised within the FIT, to enable such projects. At the Diplomat, Akimoto highlighted that an additional major constraint for wider wind power adoption is the lack of infrastructure that is able to distribute the energy generated back to cities across Japan. In order to close this infrastructure gap, the Japanese government announced it would invest 5 billion yen ($43.3 million) in undersea cable research that will enable offshore wind operators to distribute their energy to cities in major metropolitan cities like Tokyo.

Overcoming these infrastructure hurdles, McKinsey says, will only be possible with clear commitments of the federal government and alignment with local suppliers, that in turn will convince investors about the financial feasibility of the wind farm projects. The firm nonetheless has high hopes for Japan, which can become part of the “international scale-up club.” Scaling up the wind industry will revitalize its economy after the harsh economic woes of recent years. The IEEFA calculated that if Japan pushed forward with its renewable ambitions, including offshore wind, it could provide up to 35 percent of the country’s energy demand.

In September 2022, Power Magazine reported that Japan started to solidify its efforts to exponentially scale its offshore wind power capacity. Just a few weeks after the opening of the Akita wind farm, Siemens Gamesa, under the Green Power Investment program, was awarded the Ishikari offshore wind power project, up in the Hokkaido region. The project will realize 14 wind turbines including a 15-year service agreement. Once completed the Ishikari wind farm will deliver 112 MW of electricity.

CEO of the Siemens Gamesa Offshore Business Unit, Marc Becker, said in the press release, that the project will be an excellent opportunity for Japan to expand its energy mix with renewable energy. The blades of turbines will have an impressive diameter of 167 meters, spread across an area of 21,900 m2, built to withstand typhoons and seismic activity. Managing Director of Siemens Gamesa Japan, Russell Cato, noted that the project will be of benefit to local communities, supplying jobs and contributing to the local offshore wind industry. The project is set to start development in July 2023.

Unshackling the coal chains

It’s easy to point fingers that Japan isn’t doing enough to capture the massive potential of wind energy and is relying too much on fossil fuel imports. The country is well aware of its position in terms of energy security and that it has yet to make great leaps in renewable energy adoption. The government has endured strong lobby forces and its banking sector is heavily tied to coal and other fossil fuel investments.

Under the pressure of international commitments, it has stopped its investments in coal plants abroad. But it has to overcome decades of stalling, needing to make up for the lost time. The country has to lay down the infrastructure foundations to be able to ramp up its wind power capacity. All these efforts will have to shake loose the chains of coal addiction and mark a new dawn for Japan and the world.

Further reading

How wind power polarized Sweden

Wind power has seen massive leaps in recent decades, but one country keeps struggling to expand its capacity, Sweden....

How Denmark harnessed wind power

Denmark has become a leader in generating electricity through wind power. How did it become the renewable energy gold...

How Iowa became a leader in wind power

Iowa generated 58 percent of its energy through wind power, ranking it first in the US. How did the state reach this...

Most recent

How Myanmar lost 30% of its forest in 30 years

Myanmar is seeing deforestation rates increase rapidly. In the last three decades, the country already lost 30 percent...

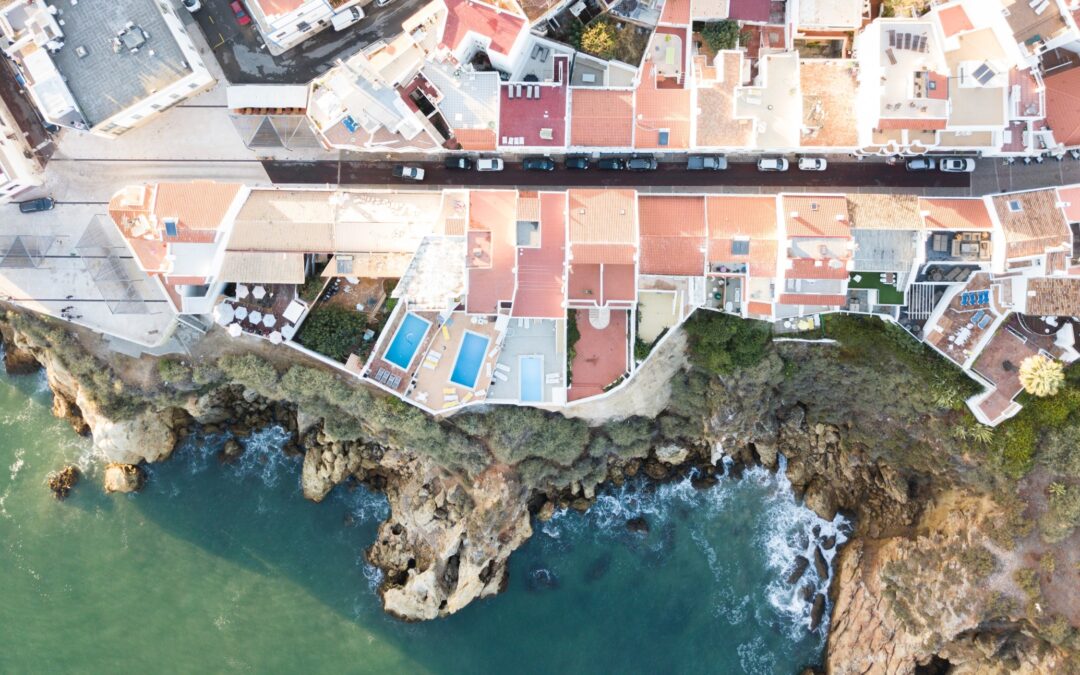

Portugal’s struggle to part with fossil fuels

Portugal is heavily reliant on fossil fuels and its love affair with the fossil fuel industry makes transitioning to...

Climate change spells uncertain future for winemakers

Winemakers ride into an uncertain future as climate change spells greater uncertainty for their businesses. Climate...