How Myanmar lost 30% of its forest in 30 years

Most recent

Myanmar is seeing deforestation rates increase rapidly. In the last three decades, the country already lost 30 percent of its forests.

Myanmar’s forests are disappearing at an accelerated rate due to an unstable political climate that has crippled the nation’s enforcement capabilities. Each year, thousands of hectares of forest disappear in order to extract resources to keep the collapsing economy afloat.

Deforestation in Myanmar

Myanmar is full of natural resources. Its lands are full of minerals, petroleum, coal, natural gas, silver, gold and much more. Extraction of its natural resources started during the 19th century, but really took flight during the 1970s, when mining activities grew exponentially. The abundance of natural resources has led to massive deforestation. Between 1990 and 2020, Myanmar has lost 27.2 percent of its forest area. Commodity driven deforestation has been the primary driver for several decades, with economic activity reaching new heights from 2009 onwards.

In 2009, Myanmar lost 215 kha of tree cover. Commodity driven deforestation accounted for 155 kha of annual tree cover loss, representing more than half of all deforestation. Urbanization represented 50 ha in 2009. The following years deforestation fell, but picked up in 2012, peaking in 2017, where the country lost a total of 362 kha of tree cover, with commodity driven deforestation accounting for 258 kha. Urbanization meanwhile had fallen to 28 ha in the same period. While the deforestation rate decreased in years to come, it remains high. In 2022, Myanmar still lost 260 kha of tree cover.

Economic incentives

In 2015, Irrawaddy spoke with Director and co-founder of environmental organization, The Economically Progressive Ecosystem Development group (EcoDev), Kyaw Hsu Mon, about the massive rates of deforestation in the country and his mission to protect fragile communities throughout Myanmar who depend on the country’s natural resources of their livelihoods. Mon has been involved in social welfare since his arrival in Myanmar in 1994, trying to help local communication reclaim forests that have been taken by the government. At the turn of the millennium, Mon and his organization focussed on preserving forests through the rule of law.

Mon points out that cutting trees can lead to a jail sentence of up to three years, with some villagers being punished for cutting trees within their own property. Imprisonment however, isn’t allowed under Forest Law, but happened nonetheless. EcoDev challenged these penalties, with cases reaching the country’s Supreme Country. The organization has also led environmental protests against the Myitsone Dam. Mon notes that deforestation is one of the most pressing issues facing the country, explaining, “It is the major factor behind environmental deterioration and has many consequences. However, people tend to care more about other, more immediate problems.” Hence, garnering support for forest protection is challenging, as poor communities are primarily concerned with water shortages and water pollution.

That doesn’t mean the general public isn’t aware of deforestation. Mon comments that there’s general awareness about environmental conservation, with the public knowing that deforestation can lead to climate change and water shortages. However, a link between deterioration biodiversity and deforestation is mostly absent. Hence, the public will need to be informed about the consequences of deforestation not in relation to the environment, but the ecosystems that keep it alive.

In 2018, Forest News spoke with Barber Cho of the Myanmar Timber Merchants Association about the worrying rates of deforestation in the country. Economic sanctions imposed on the country have led to the nation’s government resorting to its own natural resources to keep its economy from grinding to a halt. The country has breached its own forest reclamation limit, resulting in massive forest cover losses. Cho explains that the government has full rights over the country’s forest, with no other parties allowed to cut trees, unless they are granted a permit. However, the government doesn’t abide by its own limit, he added. While policies and regulations are in place, little enforcement keeps logging activities in check.

The reasons aren’t difficult to spot, the government is in desperate need to keep its economy afloat. Cho commented, “Although the highest authorities — the government — understand the value of [the] environment, they have no choice when they need (to fund) the country’s budget that they have to cut and sell logs.” Acknowledging that sanctions are necessary to punish the country for its human rights violations. However in turn, this leads to further deterioration of the country’s fragile natural resources, ultimately leading to the acceleration of climate change. This translates to political reluctance to tackle the problem head-on, Cho highlights. Deforestation cannot only be stopped if the government abides by its own rules. He hopes that the government will acknowledge the importance of forests.

Sanctions hit Myanmar

The sanctions mentioned by Cho have crippled the country’s economy and have intensified in recent years as it spiraled into chaos after a violent coup. In April 2018, the EU extended its arms embargo, which would hamper supply chains to its army and border guard police officials. The restrictions would be extended for an additional year, the European Council decided. Furthermore dual purpose goods, which can be used for military purposes, would fall under the trade restrictions. If human rights violations persits, individual travel bans would be imposed. Which happened several months later, as no improvement was detected. In June 2018, the European Union imposed sanctions on seven senior military, border guard and police officials, who have been linked to human rights violations against the Rohingya population in Rakhine State in the year 2017. These sanctions included asset freezes and travel bans.

In March 2021, the European Union and the United States imposed further sanctions on groups and individuals who were linked to the coup in February of the same year. Policymakers were appalled by the violence that came with the coup, sparking a debate to limit access to assets by those involved. Director of the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, Andrea Gacki, said the violence against peaceful protesters had to end. Adding that it stood together with the people of Burma.

In July 2023, the EU introduced its seventh round of sanctions, hitting six individuals and one entity who are involved in the quickly deteriorating political situation in the country. Among the six individuals is the Quartermaster General and policymakers, including three Union Ministers for immigration and population, labor and health and sports and two members of the State Administration Council (SAC). The state-owned No. 2 Mining Enterprise (ME 2) has been sanctioned as well, as its earnings are used for the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw). The European council highlights that thus far, it has sanctioned 99 individuals and 19 entities. The February 2021 coup resulted in more than 6,000 civilian casualties since, with the country now once again in a spiral into economic oblivion.

Political instability in Myanmar

The rising political tensions in the country have led to a strong increase in deforestation according to satellite data collected and analyzed by the University of Maryland in August 2021. Researchers found increased activity in the northern region of Tanintharyi and in the southern part of the country. Palm oil, rubber production, infrastructure and small-scale agriculture are the primary causes of deforestation, Mongabay highlighted. Palm oil is a major contributor to deforestation in countries such as Indonesia. Paradoxically, the government has established reserves, but are more a guise for other destructive projects and a way for the dictatorial government to exert control over contested regions, dislocating ethnic groups.

In November 2023, Joydeep Gupta from The Third Pole spoke with Ashley South, who’s been researching Myanmar for many years through his work at Thailand’s Chiang Mai University and his commitment to safeguard the precious forests throughout Myanmar. The interview comes during a time of great political instability in the country with attention shifting away from forest preservation. South notes that the previously ruling National League for Democracy party, had little regard for the environment. While small steps have been made to protect the forest, the political unrest has once again opened the gates for illegal deforestation.

The acceleration of tree cover loss is primarily economically driven. South explained, “Under the junta, the economy is effectively collapsing. And the junta is very much in need of cash to support the military machine and to keep running the militarized state.” Adding that logging and mining concessions have been hastily granted to maximize resource extraction. This in turn leads to consistent deforestation. An important factor is the demand in China, which further incentives the government to maintain resource extraction. South notes that China is more inclined to environmental protection. This doesn’t mean that China has strong motivations to protect Myanmar’s fragile ecosystem, it merely stepped into the vacuum that the West had left open, he added.

On top of economic incentives, the armed forces in Myanmar themselves are greatly involved in logging and mining activities to purchase arms and to compensate for the lack of humanitarian aid it receives. As the armed forces move further into the country, local communities are shattered, South comments. These communities are a vital part for forest protection, but as support cannot seep through the unstable political climate, they have little means to resist.

Climate change catastrophe

The inability to protect the nation’s forests might result in the country potentially spiraling into an uncertain future where it is unable to protect itself from the effects of climate change, Alex Lo from the Victoria University of Wellington and Shar Thae Hoy argued. Lo highlights that the country is a climate change hotspot due to its tropical climate, long coast lines, varied topology and large population. These factors combined make Myanmar susceptible to climate disasters as cyclones are expected to become more frequent in the region. Increased rainfall, combined with extended drought periods, will pose an immediate threat for the fragile agricultural sector.

Before the violent take-over, Lo points out that the government was committed to tackling climate change, even drafting its own National Climate Change Strategy in 2019, which laid down a strategy to prepare the country for shifting weather partners. After the coup, however, governmental policies shifted, were disrupted and focused on control over its territory. Environmentalists and activist groups faced budget cuts and security risks, as its activities could now interfere with state-owned enterprises. Hence, they were forced to shift their focus to humanitarian aid instead. A far less dangerous endeavor than opposing policymakers in their hunt for revenue.

The lack of climate policies that will lead to further environmental destruction is amplified as Myanmar’s citizens are being displaced due to persistent political unrest. Lo cites figures from the UN that found that over 1.6 million people have been involuntarily forced to leave their local communities, becoming illegal residents who have lost their livelihoods. They now congregate in already impoverished areas, where they are vulnerable to environmental disasters. Their situation will only worsen over time, as they are not officially recognized by the government, unable to access much needed funds to safeguard them for potential disasters. Combined with the economical sanctions that will deplete the government of its monetary resources, displacement and loss of ecosystems will persist for the foreseeable future.

Challenges in Myanmar

Deforestation has been persistent for decades in Myanmar and has been accelerating during the 2010s as demand from its Chinese trade-partner soared. Hundreds of thousands of hectares of pristine forest have disappeared. All cleared to make way for mining activities in its resource rich soil. Oversight is riddled with atrocities, corruption and economic incentives, keeping state-owned enterprises in business. The situation has been deteriorating after sanctions imposed by major economies after the violent coup, which pushed the country over the economic edge. Its government, now strapped for cash, is relying more and more on its own resources to keep itself afloat. It’s a paradoxical situation where policymakers try to punish the country for crimes against its people, while simultaneously its natural resources are under more stress than ever before.

Further reading

The fight over Poland’s forests

Poland is home to many pristine forests. But the right-wing government has been trying to resume logging in these...

Global warming threatens Midwest agriculture

Agriculture throughout the American Midwest is under threat from climate change. How will changing weather patterns...

How California plans to improve air quality

California has the poorest air quality in the United States. How does the state plan to improve air quality? In...

Most recent

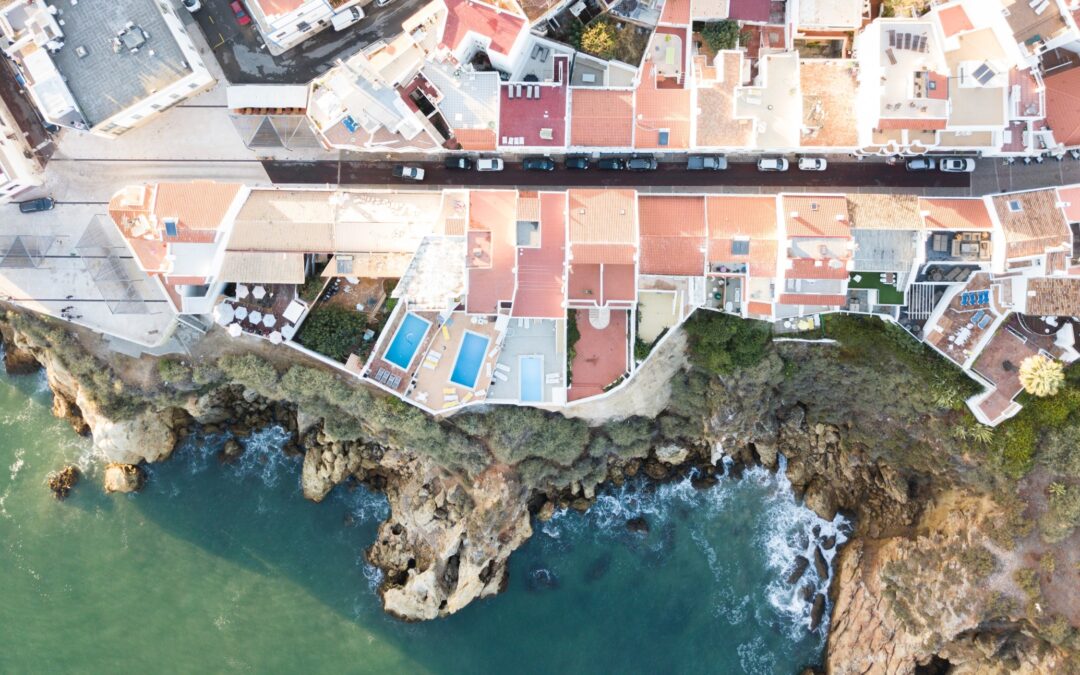

Portugal’s struggle to part with fossil fuels

Portugal is heavily reliant on fossil fuels and its love affair with the fossil fuel industry makes transitioning to...

Climate change spells uncertain future for winemakers

Winemakers ride into an uncertain future as climate change spells greater uncertainty for their businesses. Climate...

How Microsoft aims to make its data centers more efficient

Microsoft is rapidly expanding its data center fleet, whilst simultaneously experiencing soaring energy costs and...